Written by Community Engagement Manager, Kim Kneeland

Since itΓÇÖs been more icy and wintery recently, we figured it would be appropriate to shine a light on one of the key historical assets we have at the farm – the ΓÇ£Ice HouseΓÇ¥ and the industry behind it.

The ice harvesting industry began in the early 1800s in the Boston area. Fueled by demand in Europe, time from off-season farmers, and development of specialized harvesting tools, this industry became a huge part of the New England economy throughout the 1800s, only to disappear by 1930 with the introduction of refrigeration. But we can still find traces of this industry all over.

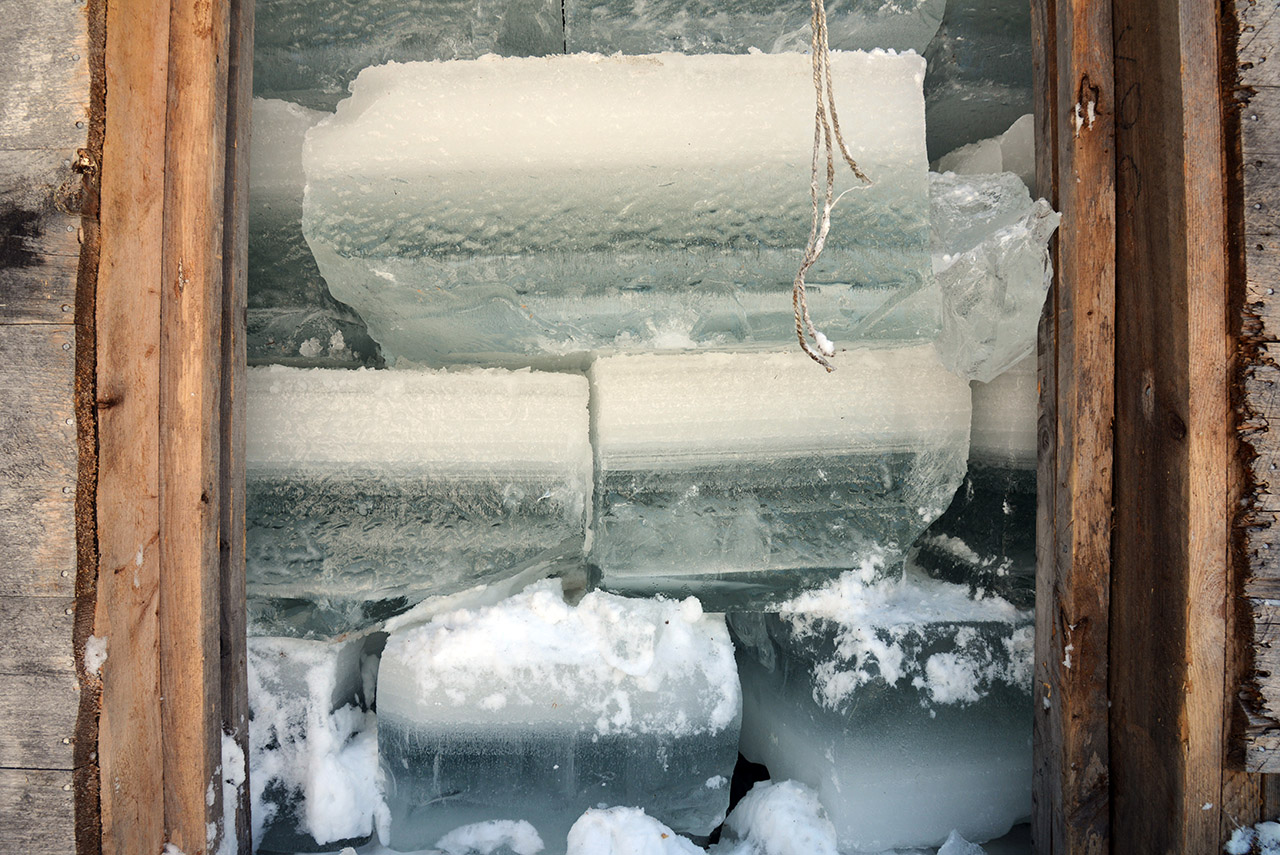

You may have noticed the small, windowless building tucked next to the 1827 Barn during your Farm visits. Well this structure was a uniquely designed, insulated ice house where large blocks of ice were packed tightly and stored for sale during the warmer months. These blocks were harvested with horse, sleigh, saw, ice picks, a lot of careful calculations, and sheer hard work.

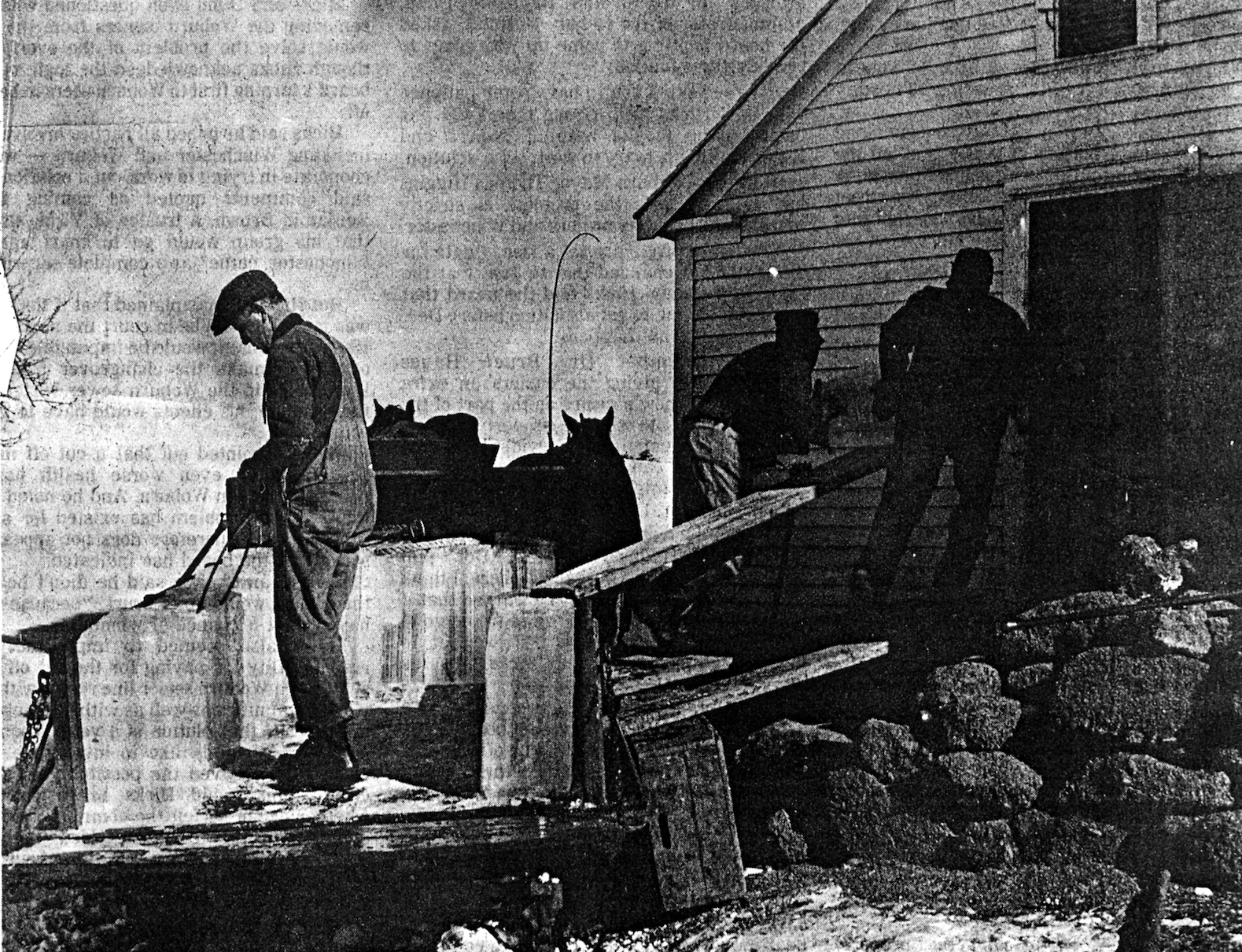

Photo c. 1920 of the Lockes loading ice into the ice house. Photo Courtesy of the Winchester Archival Center.

I think seeing photos of this process really catches peopleΓÇÖs interest as it is a very dynamic task that took community, strength, finesse, and ingenuity. Simple in its concept, there is still something so mesmerizing about ice harvesting. If you are interested in learning more, Wright-LockeΓÇÖs ice house currently serves as a mini-museum that highlights this craft, with tools, pictures, and explanations of the process (Thanks to our Historic Committee, volunteer, and board help). You can also see photos and read a great account of a modern day ice harvest in this great article originally published in Edible Geography by Nicola Twilley about the Thompson Ice House and Harvesting Museum.

The Ice House at WLF can be viewed by appointment, or during community events at the Farm. E-mail info@wlfarm.org to inquire about visiting Wright-Locke Farm’s Ice House.

Ice blocks (or cakes) were scored in a grid layout on the nearby ponds, sawed and cracked from the surrounding ice, then carefully guided through the open water channels to the sleigh to be brought to the nearest ice house. Ice harvesters would then have to muscle and maneuver the ice cakes into the house and pack, position, and stack the ice so as to fill the house just right. When filled correctly, an ice house might only lose 25% of the ice to melting over the course of the hot summer. How? Thermal mass, using sawdust filled walls for insulation, and a pitched roof to ventilate the heat that rose from any melting ice. Naturally frozen ice also has fewer air bubbles than most of our artificially frozen ice, which also leads the ice to last longer.

Bringing ice (early 1900s) from one of the nearby ponds back to the Locke Farm . Photo Courtesy of the Winchester Archival Center.

The photos below are all credited to Nicola Twilley and document the Thomson Ice House Museum’s ice harvest in 2014.