We would like to acknowledge and pay our respects to the Indigenous peoples who stewarded the land around Wright-Locke Farm for generations. This area is the homeland of the Indigenous Massachusett Tribe and Pawtucket people, who were forcibly removed in the 1600s. The Massachusett Tribe and people with Pawtucket ancestry continue to live throughout the Commonwealth of Massachusetts today. We invite you to join us in unlearning the harmful narratives and practices that perpetuate the oppression of Indigenous peoples.

Pre-colonial History

We are still learning about the Indigenous history of our area. This writing reflects the most accurate information we have at this time. If you have feedback or insight, please share with us by emailing info@WLFarm.org.

The area around Wright-Locke Farm is the homeland of the Indigenous Massachusett Tribe and Pawtucket people (who did not organize as a tribe). Contrary to colonial notions of untouched wilderness, the Massachusett Tribe and Pawtucket people actively stewarded the land, burning woodlands to facilitate the growth of grass and understory plants to improve edible harvests and game hunting. The Massachusett and Pawtucket would also plant crops including maize (corn), beans, squash, Jerusalem artichokes, and tobacco in small and large fields.

Many agricultural practices have roots in Indigenous farming, such as natural fertilizing and companion planting, and are actively practiced on farms today, including Wright-Locke Farm. For example, some Indigenous tribes would fertilize their crops with herring and companion plant corn, climbing beans, and squash.

Starting with colonists’ deliberate erasure of Indigenous history, systemic oppression of Indigenous people in North America continues today. While we are still learning how the Massachusett Tribe and Pawtucket people used the area in and around modern-day Wright-Locke Farm, historical accounts record that Indigenous people lived, hunted, planted, and fished nearby, especially by the western edge of the Mystic Lakes.

In 1636, a local Massachusett Tribe leader known by her title of the Squaw Sachem (her name was not recorded), signed a deed giving a portion of the land “against the ponds at Misticke” to Jotham Gibbons after the Squaw Sachem’s death. In 1639, the Squaw Sachem signed another deed selling much of the remaining Massachusett land to the Town of Charlestown. While this deed preserved some of the territory immediately west of the Mystic Lakes for the Squaw Sachem and her people, there was a provision in the deed detailing that after the Squaw Sachem’s death, Charlestown could “dispose of” and forcibly remove the Indigenous inhabitants to depart from their land.

It’s important to note that many early colonial deeds throughout the United States, written in English and upheld by colonial governments, would often include provisions that favored colonial land ownership. Further, according to the Massachusett Tribe’s website, “The sale of land was an unheard of concept for the Indigenous Massachusett.” While we cannot speculate whether or not the Squaw Sachem understood that the Town of Charlestown would forcibly remove the Massachusett people from their land after her death, it’s important to note that it was common for property sales and deeds, such as the ones the Squaw Sachem signed, to take advantage of Indigenous inhabitants and favor colonial interests, including colonial land ownership.

As colonization continued, the Indigenous people of the land faced more stressors and pressure. By 1644, the Squaw Sachem signed a treaty of submission, agreeing to abide by the English colonial government, jurisdiction, and religion. After the Squaw Sachem’s death in 1650, the Town of Charlestown forcibly removed the surviving Massachusett Tribe members. Upon the Squaw Sachem’s death, her youngest son brought a lawsuit to the Massachusetts General Court to possess lands that he was entitled to, but the court never obliged. The Squaw Sachem’s son was later taken prisoner in King Philip’s War and enslaved in the West Indies.

The Massachusett Tribe is active today. While the Pawtucket people do not currently exist in any organized band, tribe, or nation, members of other Indigenous tribes have Pawtucket ancestry.

We are still researching the Indigenous history of the land around the farm–the information included above is based on what we know at this time. As we learn more, we’ll update this section. We invite you to share your feedback and any insight or resources you have by emailing us at info@WLFarm.org.

Resources:

PAST OWNERSHIP (1638 – 2007)

Wright-Locke Farm had its settler origin in a 1638 decision by the Town of Charlestown to establish a new community to the northwest. One of the original settlers of the new site, in an area known as Waterfield, was John Wright. He and his descendants owned and operated the farm until 1800, when Philemon Wright sold the farm to Josiah Locke, Sr. Philemon emigrated to Canada where he and his fellow migrants founded the first white settlement in the Ottawa region. There is a brass plaque on the farm presented by the Canadian government commemorating this important event in Canadian history.

Josiah passed the farm to his son, Asa, in 1804. Asa erected the present farmhouse on the site of an earlier Wright house in 1828. He gradually expanded the farm to 182 acres, developing extensive market gardens and orchards. In 1872 he divided the property between his two sons, Josiah and Asa, with the house, farm buildings and approximately 100 acres (some of them over the line in Lexington) retained by Josiah. Following Josiah’s death in 1899, the property passed to his son, George, who continued to operate the farm as a market garden.

Josiah passed the farm to his son, Asa, in 1804. Asa erected the present farmhouse on the site of an earlier Wright house in 1828. He gradually expanded the farm to 182 acres, developing extensive market gardens and orchards. In 1872 he divided the property between his two sons, Josiah and Asa, with the house, farm buildings and approximately 100 acres (some of them over the line in Lexington) retained by Josiah. Following Josiah’s death in 1899, the property passed to his son, George, who continued to operate the farm as a market garden.

Around 1920, eager to capitalize on the growing demand for fresh produce year-round, George put up a structure specifically designed to store Blue Hubbard squash over the winter months. Well-ventilated, centrally heated, and filled with sturdy racks, this Squash House, as the building is properly known, could hold an estimated 200 tons of Blue Hubbard squash. It is believed that the particular variety of Blue Hubbard grown at the farm was the Symmes Blue Hubbard, developed locally by a member of the Winchester Symmes family. Blue Hubbards are large squashes, weighing in at up to 50 pounds. They were particularly prized by the best restaurants and hotels in Boston. While the present day market for Blue Hubbards is not as robust, we still grow them as a homage to our past.

Following the death of George Locke in 1921, the farm passed to his two sons, Chester and Wendell. They continued limited market garden operations, gradually reducing the farm to 18 acres and the area under cultivation to nine acres. Much of the former farm land became house lots, but 30 acres of woodland, marsh and swamp lying in Lexington were acquired by that town in 1969 to become part of the Whipple Hill Conservation Area. Another 20 acres adjacent to Lexington and the Whipple Hill reservation were acquired by the Town of Winchester in 1972 and set aside for conservation in an area known as the Locke Farm Conservation Area.

In 1964 Curtis and Bertha Hamilton purchased a small piece of the farm and constructed a residence at 82 Ridge Street, adjacent to the old farm house. They continued growing a limited number of crops. In 1974, the Hamilton family purchased the remainder of the farm and moved into the main farmhouse. They eventually settled upon raspberries as their signature crop, selling them most years through a pick-your-own operation.

Modern History (2007 – Present)

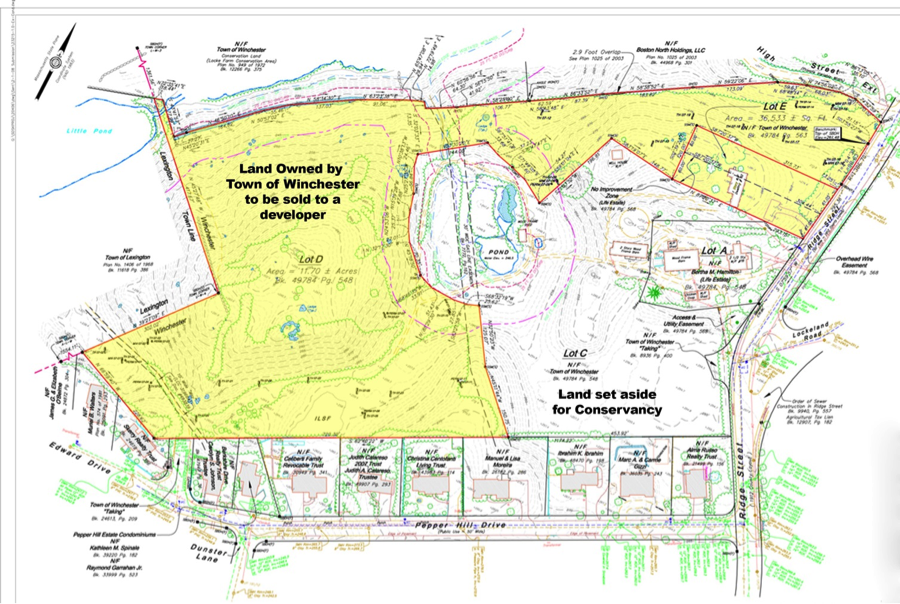

In 2007, following the death of Curtis Hamilton, the Town of Winchester passed a debt exclusion override to purchase the entire 20 acres for $14 million to prevent a private developer’s offer to construct 260 units on the Farm. At that time, the Town formed the Master Planning Committee which proposed setting aside for preservation 7.5 acres that includes the historic buildings and flat land; this carved out 12.5 acres to the north and west for potential development. Town Meeting formed the Wright-Locke Farm Conservancy, a non-profit 501(c)3 organization, to manage the property and gave it a year-to-year lease to operate the Farm. In 2011, that lease was extended to 30-years by a vote of over two-thirds of Town Meeting.

In 2007, the Town issued an RFP for development of the land and selected a developer Abbott/Engler, who offered $14 million for the 12.5 acres and received approval for 62 housing units on the parcel. That developer defaulted on its obligations in 2008 and forfeited the approvals and $1.6 million in progress payments made to the Town. In 2011, the Board of Selectmen again issued an RFP (the Abbott Plan) and received 5 bids, all of which were deemed financially unacceptable.

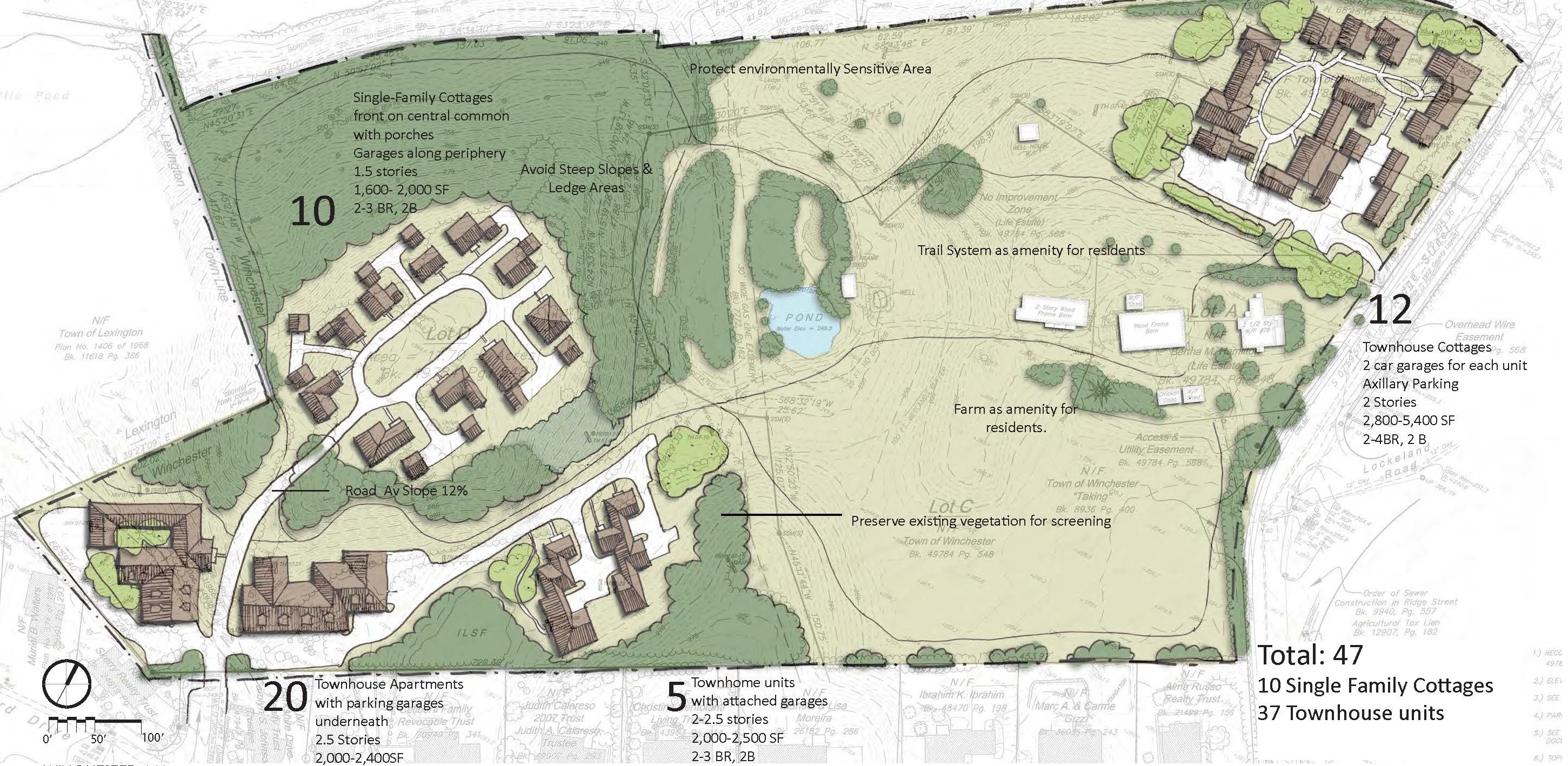

More recently, the Board of Selectmen revived the effort to develop the land around the Farm and retained the services of a development consultant, Dodson & Flinker. Dodson prepared a variety of development schemes, including the example below, allowing for a range of unit densities on the land. These plans were made public through a series of meetings, resulting in 5 different bids for the unprotected 12.5 acres; these bids included one from the Wright-Locke Land Trust which aimed to protect the entirety of the land from any residential development. In May 2015, Winchester Town Meeting members voted on the 4 qualifying bids, resulting in a 150-21 vote in favor of Wright-Locke Land Trust’s bid of $8.6 million. Learn more about the final outcome here.

With the successful purchase of the surrounding acreage, Wright-Locke and its supportive community have been able to preserve that natural space as a community resource.

Since 2015 and the purchase of the surrounding acreage, the Wright-Locke Farm Conservancy has been able to:

- create an agroforestry plan using principles of permaculture to both help conserve and utilize the diverse landscape around the farmstead

- plant a diversified fruit orchard with trees and perennials on some of that hilly 12 acres

- build a new barn with classroom, teaching kitchen, and event space called the All Seasons Barn. This heated barn will allow us to continue our educational and community programming all year long

- start a forest-based school for preschool aged children called Forest Friends

Farmstead & Architecture

The buildings and farmstead at Wright-Locke Farm are a rare showcase of early New England farm life. The six farm buildings are significant architecturally as the sole surviving complex of farm buildings in Winchester and as one of the few intact early nineteenth-century farmsteads in the Boston area.

Our four main buildings — the Farmhouse, the 1827 Barn, the Squash House and the Ice House — are listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the exteriors of the buildings are subject to a preservation agreement entered into by the Town of Winchester and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

The main farmhouse was built in 1828 by Asa Locke. Its Federal Period design is typical of many early nineteenth-century farmhouses still found throughout New England. The building has undergone many changes during its nearly 200-year history, including additions as well as having whole wings of the building removed. Its current appearance reflects sensitively rendered Colonial Revival modifications ca. 1910.

The five-bay façade (southeast elevation) is distinguished by a central entrance with a six-panel door flanked by three-quarter sidelights and surmounted by an elliptical leaded fanlight. The east and west elevations were originally identical. During much of the nineteenth century two-story ells projected from each. Both were removed ca. 1910. At that time, the current one-story porch with a shed roof and flared square posts was added onto the east elevation.

The interior is designed around a central hall plan. Rooms are finished with Federalist, Greek Revival and later Colonial Revival trim. Most of the doors, sashes and second floor mantels are original, though interior window shutters have been removed. In the cellar, two chimneys terminate in two high arches. The unusual height of the cellar, almost nine feet, suggests that it was used to store produce.

A frame barn erected in 1827 stands to the west of the farmhouse. The 1827 Barn is the largest structure on the property measuring 70′ x 40′ x 30′. The structure is sheathed in clapboards and small six-over-six windows that provide some light to the interior. Ramps lead to vertically planked double doors located in each gable end. The double doors open onto a magnificent central bay that houses some of our historic wagons. The interior has stalls for six horses and two cows. Much of the framing is hand-hewn.

An icehouse constructed ca. 1900 and measuring 17′ x 19′ x 15′ is tucked against the north side of the 1827 Barn. Its double walls were once insulated with sawdust and the exterior walls are sheathed in clapboards. The building was used to store ice harvested from ponds on the farm. An illustrated history of ice farming on the property is posted in the 1827 Barn.

The Squash House is perhaps our most unusual building. This frame structure stands to the west of the 1827 Barn and was constructed by the Locke family ca. 1915. Known as a Squash House, not barn, this building was specifically designed for over-winter storage of blue hubbard squash grown on the farm. It is reported to be one of the only buildings of its kind still remaining in Massachusetts. The Squash House has many unusual features. Immediately noticeable are the great number of windows on all four facades allowing significant light into the structure.

The building has a heating system that kept the squash just above freezing temperature. Undoubtedly the most unusual feature is an entire second floor outfitted with tiers of full-height racks designed to store blue hubbard squash.

Other buildings on the property include a late nineteenth-century wagon shed which houses our chicken coop and a small frame early twentieth-century garage that now serves as our farm stand.